About Hearing Loss

Most people understand hearing loss as an ear problem. But that’s only half the story.

Hearing actually happens in two places: the ears and the brain. When hearing loss occurs, the issue isn’t just volume; it’s also in the brain’s ability to interpret and make sense of sound.

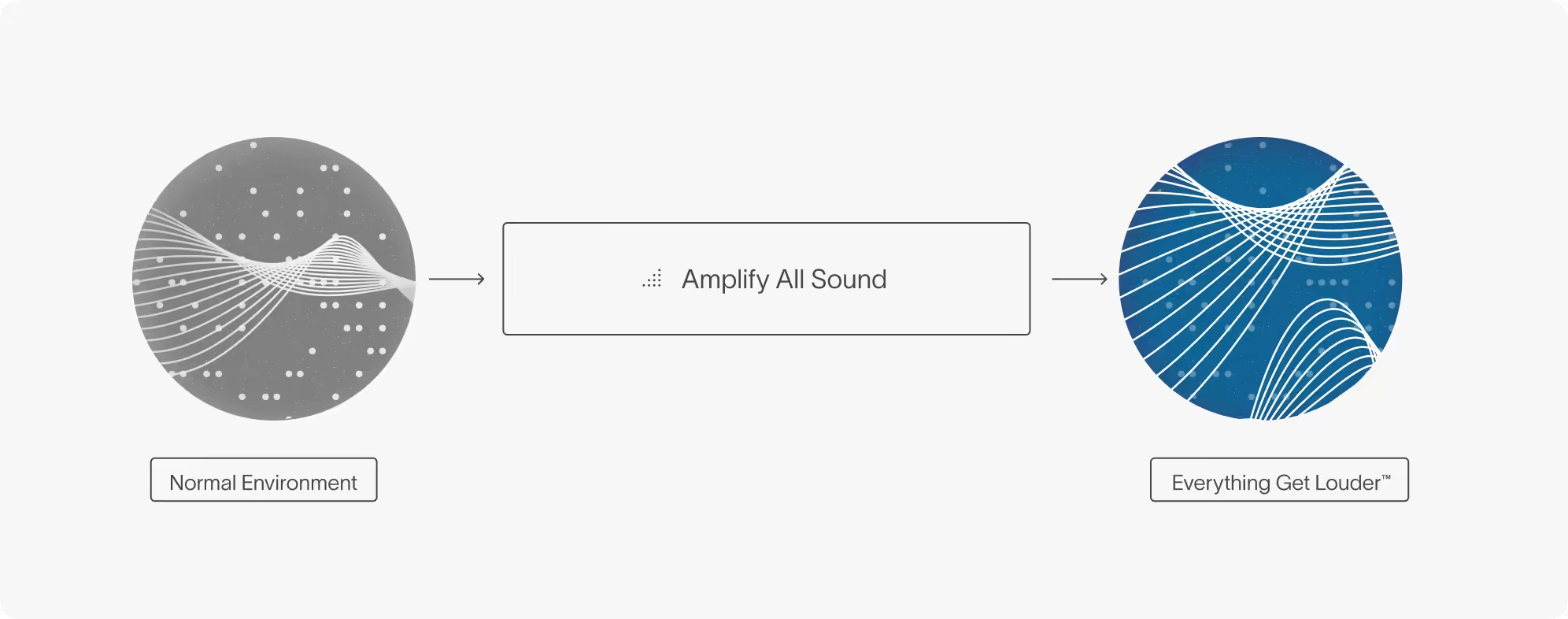

Traditional hearing aids amplify everything—they solve the ear problem. But they don’t improve the brain’s ability to separate speech from noise, especially in the places people struggle most: loud restaurants, busy streets, and crowded conversations.

Fortell is the first hearing aid that’s meaningfully changing that. We’re building hearing technology that helps the brain decode speech. Not just making it louder, but making it more intelligible so you don’t just hear more, you understand more.

Hearing is about the ear and brain connection.

The auditory process begins when sound waves enter the outer ear, funneling through the ear canal and causing the eardrum to vibrate. These vibrations are transmitted via the ossicles in the middle ear into the cochlea in the inner ear, where specialized hair cells convert vibrations into electrical signals.

These electrical signals travel along the auditory nerve to the auditory cortex located in the temporal lobe. Here, the brain decodes, organizes, and interprets the incoming signals into meaningful sound. The health of both these components—the peripheral auditory structures (ears) and the central auditory pathways (brain)—is critical for effective hearing.

The most common form of hearing loss, sensorineural hearing loss (known as presbycusis), affects approximately 1 in 3 adults aged 65 to 74 and nearly half of those aged 75 and older.¹

This condition significantly impacts the brain due to fewer and weaker auditory signals reaching the auditory cortex. Reduced auditory input forces the brain to work harder to interpret sounds, causing difficulties with audibility and clarity, especially for high-frequency sounds crucial to speech intelligibility.²

Untreated hearing loss erodes connection and contributes to poorer health outcomes.

Because hearing difficulties are easy to overlook, many people delay seeking help. But their brain is working overtime to piece together incomplete auditory information. This sustained effort taxes cognitive resources, leading to reduced memory, concentration, and mental clarity.

Over time, this invisible friction takes a toll. Research consistently links untreated hearing loss to social isolation, reduced participation in activities, and a heightened risk of depression and cognitive decline.3,4 When patients struggle to hear during medical appointments, they are more likely to misinterpret diagnoses, medication instructions, or follow-up plans. For older adults managing multiple health conditions, even a small misunderstanding can lead to serious complications. Research shows5 that older individuals with hearing loss are more likely to experience hospitalizations, longer stays, and higher readmission rates, because of the cascade of miscommunication hearing loss creates.

The biggest problem for today’s hearing aids? Background noise.

Over the past century, each generation of hearing aids has improved the user experience but also revealed limitations that future devices would try to overcome. While today’s hearing aids are sleek, connected, and personalized, the core processing model hasn’t fundamentally changed since the 1990s.

Modern hearing aids can recognize different environments and automatically adjust how they process sound. Still, the most critical challenge remains unresolved: distinguishing speech from background noise.

Today’s hearing aids still rely on processing sound based on frequency, amplitude, and timing. That’s useful for filtering out a gust of wind or softening the clatter of dishes. But in challenging environments, particularly where voices overlap, it’s all just undifferentiated sound energy from the device’s perspective. Even top-tier devices struggle when the background noise is other people’s voices. Directional microphones and noise suppression algorithms help at the margins, but they can’t identify what matters to the listener. Traditional hearing aids have gotten smarter about managing sound. But true innovation lies in organizing it not just for the ear, but for the brain.

Fortell’s hearing technology separates speech from background noise, reconnecting people with the world.

Instead of relying solely on the physical properties of sound, our technology uses advanced AI models trained on millions of real-world audio examples to understand what sounds are and what matters to the listener. Now, finally, a hearing aid can make decisions both based on how sound behaves and on what those sounds mean. Solving this demanded a new kind of machine, one that could interpret sound with human-like nuance. That meant building a device that could:

1. Understand sounds via deep neural networks

Using deep neural networks trained on millions of real-world audio scenes, Fortell can recognize the meaning of sound in context: distinguishing speech from background chatter, environmental cues, or irrelevant noise. It combines two key capabilities:

- Semantic understanding: Large-scale AI models categorize sounds in real time, identifying speech, noise, and environmental cues to prioritize what the wearer needs to hear.

- Spatial spotlighting: By analyzing input from dual microphones, the system recognizes where sounds are coming from to boost speech from in front of the listener while reducing interfering voices from other directions.

Together, these capabilities enable true source separation: the ability to disentangle overlapping sounds and selectively amplify only the most important speech.

2. Pack that intelligence into a form small enough to fit discreetly behind the ear

Running deep neural networks in real time typically requires the computing power of a smartphone or server. Achieving that within the size, power, and thermal constraints of a behind-the-ear hearing aid required a custom solution.

Fortell designed a proprietary AI chip purpose-built for semantic and spatial sound processing — delivering vastly more compute than any prior hearing aid, while maintaining all-day battery life.

3. Process all of it instantly, with zero perceptible delay

Real-time conversation demands real-time processing. With Fortell AI Hearing Aids, speech sounds stay natural, synchronized, and easy to follow in complex soundscapes.

This combination of breakthrough AI and breakthrough hardware moves hearing technology beyond amplification and closer to true human listening. Fortell AI Hearing Aids interpret sound based on meaning to prioritize what matters and resolve the real challenge: helping the brain make sense of sound instead of simply providing more volume. We’re proud to reconnect people with the world and give them a path to clarity.

¹ Gates, G.A., & Mills, J.H. (2005). Presbycusis. The Lancet, 366(9491), 1111-1120

² Neuroanatomical changes associated with age-related hearing loss and listening effort

³Hearing Loss in Older Adults Affects Neural Systems Supporting Speech Comprehension